The family of an Army reservist who perpetrated a deadly mass shooting in Maine told a state commission Thursday that he had a “severe” traumatic brain injury tied to his service as a hand grenade training instructor, and that the military has begun a “psychological autopsy” of his life.

Robert Card was found dead by suicide after killing 18 people at a Lewiston bowling alley and bar in October. In the aftermath, his family donated his brain to the Boston University CTE Center, which said in March that there was “evidence” of a traumatic brain injury and its findings aligned with previous studies on the effects of blast injuries.

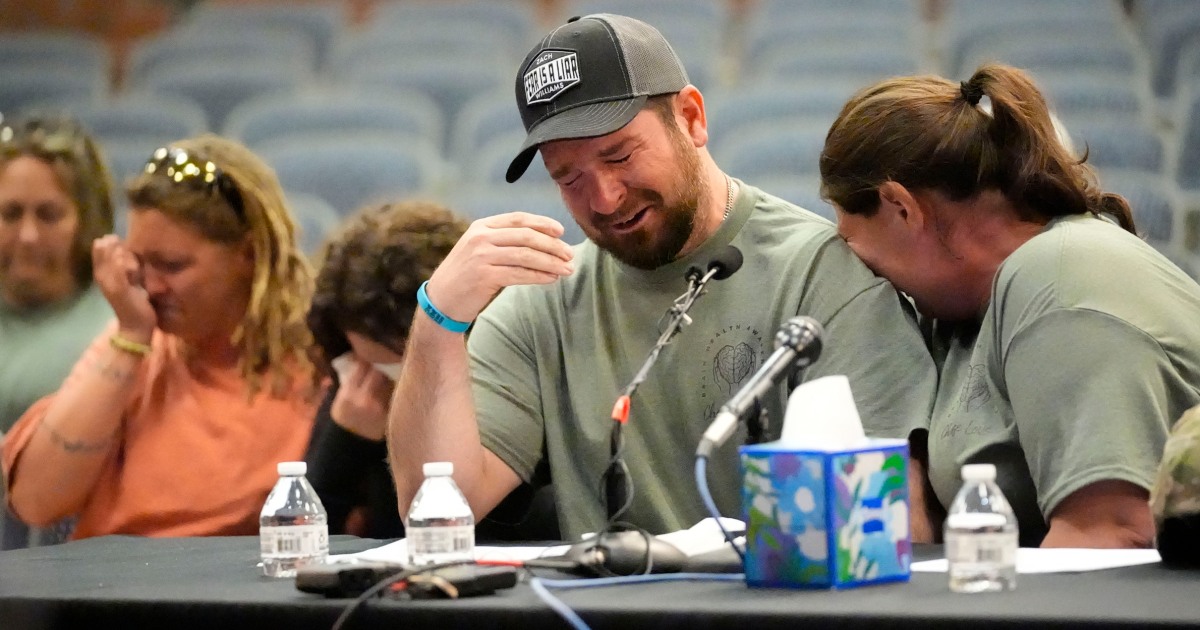

“We have discovered that Robbie had a severe, a severe traumatic brain injury,” James Herling, the gunman’s brother-in-law, told an independent commission that has been investigating the shooting since late November and is scrutinizing whether enough was done to prevent the massacre.

The family members said researchers who studied his brain told them it was “one of the worst” cases they had seen — even in comparison to military personnel who had served in Afghanistan and Iraq.

But the 40-year-old shooter “was not an active soldier, he was a reservist,” Herling said, adding that “his brain was not healthy, and no one knew.”

“My brother-in-law was not this man — his brain was hijacked,” he said during his testimony, in which he repeatedly choked back tears.

Nicole Herling, the shooter’s sister and Herling’s wife, told the commission that she began discussions last week with a forensic psychologist at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, one of the military’s foremost hospitals, to better understand her brother’s background and potentially find patterns that can help others.

A spokesperson for Walter Reed did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Nicole Herling said she noticed a change in her brother’s demeanor in the months before the shooting, but believed he was more of a threat to himself than to others as he grew paranoid that people, particularly at his job at a recycling center, were speaking negatively of him. The shooter had pushed his family away, his loved ones said.

“I never in my wildest dreams could have imagined the act that he did,” Nicole Herling told the commission.

“I wish I had done everything in my power to get him the help he needed,” Herling said.

She added: “He didn’t believe me when I said he was sick, not crazy.”

The shooter had been an Army reservist for two decades and was a longtime hand grenade training instructor. Family members said they had tried to reach out to the Army given their concerns about his mental health last year and access to guns, but that their calls went unreturned or unanswered.

The family learned in July that he had been hospitalized in a psychiatric unit for two weeks as a result of shoving another reservist and isolating in a motel room during a training in New York. Upon his release, he was prohibited by the military from accessing weapons while on duty. But there was another warning sign that he could be a danger when a fellow reservist and former roommate texted an Army supervisor a month before the rampage, writing: “I believe he’s going to snap and do a mass shooting.”

In March, the independent commission’s interim report found that a Sagadahoc County Sheriff’s Office sergeant could have done more to seize the shooter’s firearms, and had enough reason to initiate the state’s “yellow flag” law, which allows law enforcement to confiscate a person’s firearm if they are believed to be a threat to themselves or others.

At a hearing in March, military officials deflected some of the blame onto local law enforcement. Army Staff Sgt. Matthew Noyes said the “responsibility fell” on those agencies to do something to access the shooter’s weapons from his home since he was no longer on the base.But Nicole Herling said Thursday that her testimony was “a call to action” for the Defense Department to better address the issue that low-level blasts may have on soldiers.

“Here, I brought the very helmet meant to safeguard my brother’s brain,” she said, showing the commission the military headgear. “To the Department of Defense: It failed. It’s been failing.”

Nicole Herling stressed that her brother’s traumatic brain injury findings don’t fully explain his actions and that a brain injury doesn’t mean someone is more likely to commit such violence. Boston University researchers had said they found no evidence the shooter suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, a degenerative brain disease associated with behavioral and cognitive issues related to repeated head injuries.

But the shooter’s sister said she hopes that the military will use his case to help train others to recognize the signs and symptoms of a traumatic brain injury.

Her brother’s “fear of appearing mentally unstable likely exacerbated his condition,” she added.

Dr. James Stone, an imaging expert at UVA Health previously enlisted by NATO to help develop guidelines for preventing serious brain injuries in service members, told NBC News in March that “we need to, as soon as possible, answer the question of how much is too much when it comes to safe levels” of low-level blast exposures.

The Army said Thursday that it is “committed to understanding how brain health is affected” and that soldiers can receive treatment even if there is no “single identifiable event” linked to a perceived injury.

Beginning next month, “baseline cognitive assessments will be conducted on trainees at Initial Entry Training and repeated at least every five years to identify changes in their cognitive abilities,” Army spokesperson Bryce Dubee said in an email. “In addition, the Army is developing and evaluating improved protective equipment to minimize blast exposure.”

The Army inspector general’s own independent review involving the Lewiston shooter’s actions preceding the massacre is ongoing, Dubee added.

Commissioners at Thursday’s hearing, which was steeped with emotion, thanked the shooter’s family members for being open about their struggles. Herling said he has the names of all the shooting victims on a wall of his family’s home “as a constant reminder.”

Cara Lamb, the shooter’s ex-wife who shared a son with him, testified that the pair weren’t close and that she has been unable to pinpoint a motive for his actions.

“We could ask a million whys for the rest of our lives and never have a good enough answer,” she said.

But, Lamb said, she hoped that whatever directive comes from the commission’s final report will ensure that people facing mental health crises are being helped.

“I don’t want to point my finger at any of them and say that this is on them,” she said of the military, law enforcement and others who interacted with the shooter, “because I firmly believe it’s on all of us from this point forward.

“I’m his ex-wife. He was not a fan of me,” Lamb said. “But it’s on me, too.”