The Food and Drug Administration this week told several drugmakers to add a boxed warning — the agency’s strongest safety label — to the prescribing information for a type of cancer treatment called CAR-T therapy, saying the treatment itself may increase a person’s risk of cancer.

Carly Kempler, a spokesperson for the FDA, said that, despite the warning, “the overall benefits of these products continue to outweigh their potential risks.”

The agency’s decision to update the labels was based on reports of rare blood cancers in patients who had previously gotten CAR-T therapy, Kempler said. As of Monday, the agency had received 25 reports of the blood cancers in CAR-T patients, she said.

Bruce Levine, a professor in cancer gene therapy at the University of Pennsylvania, said that in addition to the reports submitted to the FDA, two abstracts published late last year in the journal Blood also cited a potential cancer risk associated with CAR-T therapy, which likely “forced the FDA’s hand.”

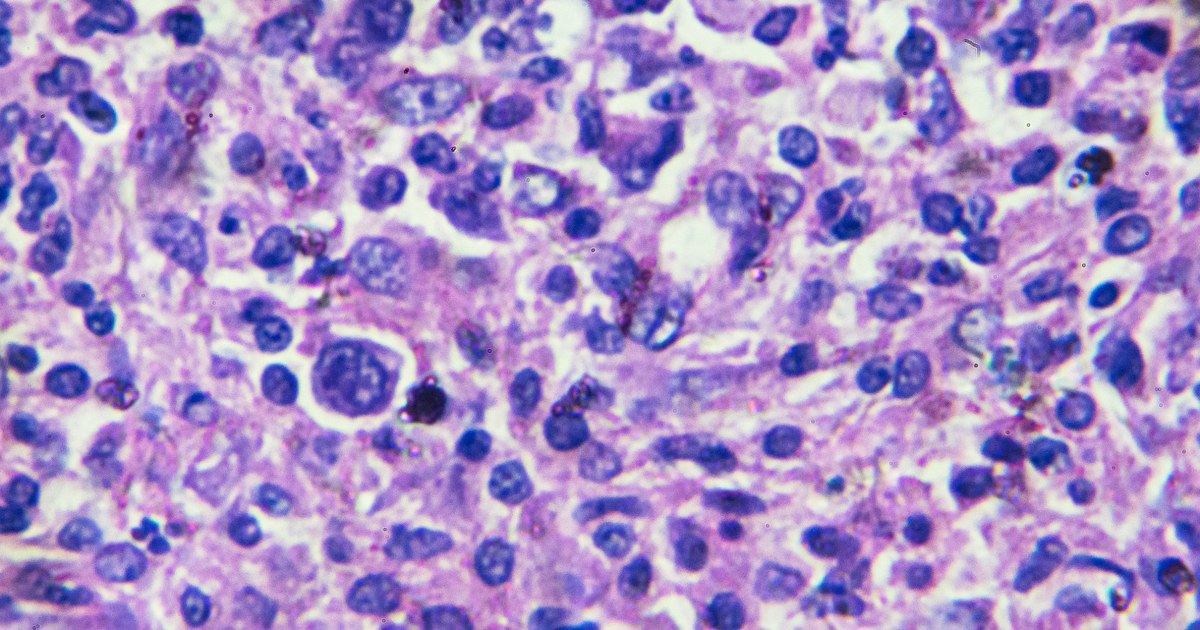

CAR-T — or chimeric antigen receptor T cell — therapy uses a patient’s own immune cells to treat certain blood cancers, such as leukemia, multiple myeloma and lymphoma. It involves harvesting the immune cells — in this case, T cells — then genetically altering them in a lab to make them target cancer cells, and finally reinfusing them back into the patient.

It’s proven to be highly effective in hard-to-treat cases, experts said. In 2022, doctors who had treated two leukemia patients with CAR-T a decade ago said it was fair to say the therapy had cured the patients of the disease.

“This has been a game changer when we think about treating lymphoma and other diseases,” said Dr. Matthew Frigault, the clinical director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Cellular Immunotherapy Program in Boston.

The first CAR-T therapy, Novartis’ drug Kymriah, received FDA approval in 2017. Since then, another five have been approved.

The makers of the drugs — Bristol Myers Squibb, for Abecma and Breyanzi; Gilead Sciences’ Kite Pharma, for Yescarta and Tecartus; Johnson & Johnson’s Carvykti; and Novartis, for Kymriah — received letters from the FDA, stating that they must submit proposed label changes in the next 30 days to note that, in rare cases, CAR-T therapy can increase the risk of rare blood cancers.

If the drugmakers disagree, they can instead submit a rebuttal explaining why a change isn’t needed.

In a statement to NBC News, a spokesperson for Novartis said the company has not found “sufficient evidence” to support a link between cancer and its treatment, which has been used in more than 10,000 patients. However, the spokesperson said, the company will work with the FDA to update its label “appropriately.”

Spokespersons for Johnson & Johnson and Gilead Sciences also said the drugmakers would work with the agency to update their labels.

A spokesperson for Bristol Myers Squibb said the company is evaluating “next steps” following the FDA’s notice, although it has not seen any cancer cases associated with its treatment.

“Patient safety is our top priority,” the spokesperson said.

How might CAR-T therapy cause cancer?

Still, there’s the question of how CAR-T could cause cancer — if it does at all.

“We actually don’t know whether this is causal, meaning, we don’t know for a fact that the CAR-T cells in the tumor have led to this,” said Frigault, of Mass General.

CAR-T treatments are still relatively new: Frigault noted that the FDA has required that the makers of the products conduct 15-year follow-up studies to assess the potential risk of secondary cancers following treatment. (Secondary cancers are cancers that can arise from treatment.)

The FDA “is not saying that every single one of the cases they’ve reported has clearly shown CAR-T has led to this,” he said, “but more that there may be an association.”

“This is what the FDA does. They look for a signal,” he added.

If CAR-T does cause cancer, the risk is likely very small, said Dr. Hemant Murthy, a hematology-oncology physician at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida.

More than 27,000 doses of CAR-T therapy have been administered in the U.S., according to the FDA.

“I don’t really see this affecting too much of practice,” Murthy said.

Dr. Saad Usmani, a myeloma physician and cell therapist at Memorial Sloan Kettering, said the label change should support physicians’ current practice of discussing with patients the risk of developing secondary cancers following cancer treatment.

Usmani noted that other cancer treatments, such as radiation and chemotherapy, also carry a risk of secondary cancers.

“The change is expected given the recent reports, albeit very low incidence in such cases,” he said.

Dr. Marcela Maus, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the Cellular Immunotherapy Program at Massachusetts General Hospital, said physicians might be more cautious, but it most likely won’t change much in their practice.

“We need to manage the cancer that they have now, so I don’t imagine it being massively different,” she said.